Looking for information on the Seminole Indians in Florida?

When the Spanish explorers led by Ponce de Leon and Hernando de Soto arrived in what they called La Florida (covered with flowers) in the year 1513 they encountered a Native American tribe known as the Calusa who lived on the southwest tip of Florida.

After many years of conflict between the conquistadors and the white settlers, the Calusa became extinct from losses in the battle with the Spanish and diseases that decimated their tribes, and by the 1700s the only settlements remaining were at Pensacola and St. Augustine, with the rest of Florida largely uninhabited.

Seminole Indians in Florida – A Full History

Historians tell us that smallpox, measles, malaria, and yellow fever killed over 90 percent of the Native population across America, the disease being brought by the Spanish to the shores of Florida where the first white settlers encountered the Indians. The Spanish conquistadors (conquerors) were beaten back several times, but eventually, they established settlements in Pensacola and St. Augustine, and with the Muscogee and Seminole tribes migrating from the north to escape the English, attempts at treaty-making continued along with skirmishes and battles along the Florida panhandle.

According to Semtribe.com in its article “Collison of Worlds” the Spanish no longer wanted Florida and in 1819 they ceded it to the Americans under the Adams-Onis Treaty. The article also noted that Ponce de Leon was killed when he returned to Florida in 1521 to search for the mythical Fountain of Youth and that Fernando de Soto died of one of the diseases the Spanish brought with them.

Seminole Indians in Florida/ Flickr

Florida Seminoles Migration

Thereafter native Americans, mostly Creek, Muscogee, and escaped slaves who came to be called black Seminoles migrated from Alabama and Georgia to the northwestern Florida Panhandle to escape the English who were stealing their lands.

The area occupied by these tribes stretched from Mobile, Alabama to Tallahassee, and collectively the several tribes became known as the Seminole, meaning “wild ones” or “runaways” because they were masters at eluding capture from the Spanish, and later the U.S Army. They came into conflict with the U.S. when southern militias and the U.S. Army crossed into Florida to capture the escaped slaves.

As tribal settlements were burned to the ground and members scattered, the U.S. Army used hounds to track the elusive Seminole who moved farther into the swamps and everglades.

Florida Seminoles Migration/ Flickr

Seminole Tribe of Florida – Unconquered people who sought “freedom from conquest”

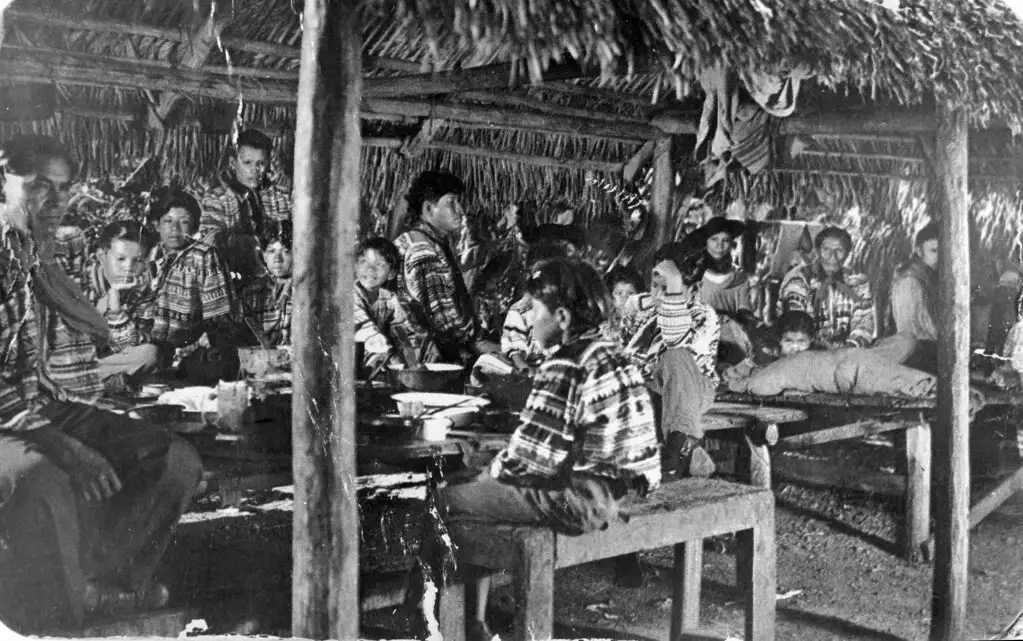

The Seminoles designated themselves as the unconquered people who sought “freedom from conquest,” and they were known for sewing, chickee building (palm-thatched houses on stilts), patchwork, and the sport of alligator wrestling.

They celebrated the changing seasons, wore ornamental clothing, and practiced their traditional forms of dance and music, and they traded leather and cattle with the Spanish and later with American settlers when East and West Florida was ceded to the U.S. in February of 1819.

The Seminoles were largely farmers and according to their traditional culture, the women grew squash, beans, and corn, while the men hunted alligators, turkeys, deer, and rabbits while others fished the rivers.

Under Threat from Attack – Seminoles Wars

The Seminoles were a peaceful tribe but when under threat of attack they displayed their warrior spirit. Abiaka, a negro war chief of the Panther Clan was considered a great medicine man and he became chief during the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) when others migrated or became too old to lead, and he led his warriors deep into the swamps when the U.S.

Army tried to capture them. Abiaka, known as Sam Jones, the chief of the affiliated Miccosukee tribe, guided the Seminoles through the swamps during the years of warfare with the American army.

He healed their sickness with herbs, and he used the tactic of “shadowing” the soldiers as they trudged through the swamp, attacking them, often from hammocks (hardwood forests of diverse trees and shrubs) which they hid behind to ambush the soldiers.

Guerilla warfare

Abiaka along with Osceola used these hit-and-run tactics or “guerilla warfare to fight the American soldiers who sought to capture him, and by doing this he resisted capture and remained elusive. Abiaka’s cook, Martha Jane, was present at a potential treaty meeting with General Worth and she quoted Abiaka as saying, “My mother died here, my father died here, and I’ll be damned I will die here too,” yelling out a traditional war cry, “Yo-Ho-ee-Hee-eei.”

Legend has it that he killed his sister when she urged him to emigrate and that he hated the white men so much that he threw down the money the army offered him to emigrate west and refused to look at them. Abiaka continued to elude capture and he eventually died in the swamp that he loved.

Billy Powell (Osceola), another Seminole warrior, was born in Alabama to a Muscogee mother and an Englishmen named William Powell. The family moved to Florida when Billy was a child, and later, having witnessed the white man’s brutality against Native Americans he joined the Seminoles and began to fight against the U.S. government’s attempt to resettle the Seminole to a reservation in Oklahoma territory.

In 1835 Osceola, though he was not a chief, together with other Seminole chiefs such as Coacooche, Jumper, Alligator, Tustunnegge, and other brave warriors revolted against a group of Seminole chiefs who signed the Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832) under which they agreed that the Seminoles would move to the lands west of the Mississippi. In response, they killed chief Charley Emathla because he was preparing to move his people to a reservation in the lands west of the Mississippi.

Seminole war 1835-1842 – Fight for independence

In the following years, Osceola and his warriors continued to fight for their independence, with the U.S. Army decimating their ranks in the many skirmishes and battles that took place in the swamps of Florida until in October 1837 when he was captured by General Jesup under a false flag of truce in St. Augustine and was then taken by ship to a prison at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina.

After he died on January 30, 1838, his doctor Frederick Weedon, cut his head off, had it embalmed, and took it home for a souvenir.

Along with his colleague, Dr. Benjamin Strobel they made a death cast of Osceola’s head and shoulders which is on display at the Smithsonian Institution. Osceola County is named after Seminole warrior Osceola and the county flag displays a picture of Osceola with a brilliant sunburst as he was often called “The Rising Sun.”

What happened to the seminole tribe? Ambush of the 4th Infantry Unit

In 1835 the remaining Seminole warriors ambushed the 4th Infantry Unit under Major Francis Dade in what became known as the “Dade Massacre.” Dade was born in Virginia and after his service in the War of 1812 as a third lieutenant, he was transferred to the military base in Key West, Florida in 1815 where he eventually led two campaigns in 1825 and 1826 in pursuit of the cunning Seminole. The two campaigns through the wilderness were successful, and in October of 1835, Dade was ordered to Ft. Brooke where he took command of 47 troops, most of whom were European immigrants. He was then ordered to march from Ft. Brooke, an outpost at the mouth of the Hillsborough River, to reinforce Fort King in Ocala.

However, Osceola and Micanopy had already destroyed the bridges over the Hillsborough River and the Withlacoochee River and were waiting in ambush for Dade and his troops. Dade and his troops were ambushed by the Seminoles who were hiding on high ground behind hammocks.

During the battle, Major Dade was killed and most of the soldiers were slaughtered leaving only two survivors. When General Dade’s remains were found at the site of the massacre, he could only be identified by the infantry buttons on his vest. In the months that followed attacks on white settlements took place across Florida which resulted in a large military buildup under General Winfield Scott.

Burial at the St. Augustine National Cemetery

General Francis Dade’s remains were buried at the St. Augustine National Cemetery along with fourteen hundred other soldiers who were buried in mass graves. Today the area is marked by the Dade Battlefield Historic State Park in Bushnell, Florida, and the Dade Monument in West Point Cemetery at the United States Military Academy and is “composed of three pyramids, and an obelisk, and it was built with coquina stone (fragments of the shells of mollusks, trilobites, and brachiopods). Miami-Dade County is also named after him, as well as the Dade County Courthouse and several other counties and cities: Dade County, Georgia, Dade County Missouri, Dadeville, Alabama, and Dade City in Florida.

In 1836 President Andrew Jackson appointed Quartermaster Thomas Sydney Jesup to pursue the Seminoles. Jackson considered Jesup a man of action and he was ordered to capture or kill the remaining Seminoles along with the black Seminoles, the escaped slaves who had joined them in the fight.

History tells us that Jesup viewed the negroes as the key to capturing Chief Osceola, the black Seminole leader John Horse, Micanopy, and his black interpreter Abraham, as well as Coacoochee and Alligator. Jesup knew that the Seminole tribes loved their black slaves, most of whom were farmers whose only requirement was that they pay an annual tribute of part of their harvest to the Seminole Indians.

And therefore, Jesup tried to disrupt the Seminole economy by burning their villages and destroying their crops in the hope that this would force them to surrender and move to the reservation in Oklahoma.

Order for troops to kill the Seminole Chiefs

Jesup then set out with 800 troops to kill or capture the Seminole Chiefs and their warriors. He was ordered to remove the Indians from the Withlacoochee riverbanks and away from Fort King and Volusia near the St. Johns River. But the elusive Seminoles disappeared into the swamps as the soldiers approached.

The army then attacked a settlement at the Hatchee-Lustee River scattering woman and children left behind by the retreating warriors, forcing Chief Micanopy to come out of the swamp and surrender to prevent further harm to his people. Jesup was later wounded and forced to retire after leading several campaigns in which he failed to capture the Seminoles.

On Christmas day in 1837, according to the Florida State Parks website, Colonel Zachary Taylor, in the largest battle of the Second Seminole War, led 800 regular army troops, 200 Missouri Volunteers, and 50 Delaware Indians to force the Seminoles to leave their reservation north of Lake Okeechobee and move west of the Mississippi. During this campaign, he was granted permission to use bloodhounds to track the Seminoles, but as it turned out the bloodhounds did not fare too well in the everglades and swamps of Florida. In an 1838 letter, Tylor wrote:

I am decidedly in favor of the measure [using bloodhounds], and beg leave to urge that it is the only means of ridding the country of the Indians, who are broken up into small parties that take shelter in swamps and hammocks, making it impossible for us to follow or overtake them without the aid of such auxiliaries…but I distinctly wish it understood, that my object in employing dogs, is only to ascertain where the Indians can be found, not to worry them.

According to the above-quoted article “Zachary Taylor: Hunted Indians with Bloodhounds” on Indian Country Today (ICT) by Alysa Landry, Florida government officials gave Taylor five handlers and 33 bloodhounds, but the dogs were useless since they were only trained to track black slaves and could not sniff out Indians. She also writes that General Taylor was unable to capture the Seminole and resigned from his post in 1840—two years before the war ended.

Final battle of General Zachery Taylor

In the battle, approximately 380 and 480 Miccosukee and Seminole Indians led by Abiaka, Billy Bowlegs, and Tustunnegge hid on higher ground behind hammocks covered with grass and they ambushed the soldiers as they trudged through the muddy swamp.

In the ensuing battle, General Taylor forced the Indians to retreat farther into the swamp, and his unit suffered 28 soldiers dead and 112 wounded, with 12 Indians killed. A surgeon who had been in the thick of the battle was rumored to say, “Florida was a most hideous place to live in…it was a perfect paradise for Indians, alligators, frogs, and every other kind of loathsome reptile.”

After this final battle General Zachery Taylor was declared a hero and went on to win the Presidency, and the Park site tells us that at the end of the Seminole war 40 million dollars had been spent by the U.S. government, with 300 killed in action and 1,145 dying of disease. Today 2000 descendants of those 300 Seminoles who were not killed, captured or forced to migrate after the decades-long battle that culminated in the Third Seminole War (1855-1858) now live on six reservations across Florida: Hollywood, Big Cypress, Brighton, Ft. Pierce, Immokalee, and Tampa.

The Okeechobee Battlefield Historic Park marks the spot where in December of 1837 Miccosukee and Seminole warriors led by Holta Micco (Billy Bowlegs), Abiaka, Tustunnegge, and Coacoochee fought against Colonel Zachery Taylor’s troops. The battle is reenacted every year during the last weekend of February. In Hollywood, Florida there is also a Seminole Hard Rock restaurant, and there is a memorial statue of Abiaka on the Pine Island Ridge on the Miccosukee Seminole reservation known as Big Cypress.

The last of the “Five Civilized Tribes”

The Seminole tribe was the last of the “Five Civilized Tribes,” the others being the Cherokee, Muscogee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw forced to walk the “Trail of Tears.” As the groups of Seminoles who refused to emigrate after they called the Great Seminole War (1835-1842) were captured they were taken in groups overland to New Orleans to Fort Pike, then sent up the Mississippi River by steamer to Montgomery Point in Arkansas, then up the Arkansas River to Little Rock, where they were marched overland to the reservation in Ft. Gibson Oklahoma. Many died of cold, hunger, and disease along the way, and by 1830 all but two or three hundred Seminoles had been forcibly removed from Florida.

Looking back at it this “clash of civilizations” the question arises as to whether it was inevitable. Many will argue that the Native Americans were treated unfairly and forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands. But the underlying fact is that with the influx of Europeans from the East Coast to the shores of Florida the push westward was in fact inevitable.

The white settlers had arrived and many of them wanted land for farming and cattle ranching which was offered to them by the United States government and land speculators. This involved them being given lots of lands that were occupied by Indians and subsequently bloody clashes took place. The government then, seeking to help the settlers, began forcibly moving the Native Americans west of the Mississippi to designated lands.

Then came the need for railroads with the greedy railroad Barrons demanding that the government remove the Indians from railway passage areas leading to the west. During the turmoil between the Indians and the settlers, the greedy land, speculators called “jobbers” and the land companies began selling lands that were occupied by Indian tribes, often ignoring treaties that had been made giving the Indians reservations on those lands.

They distributed literature across America and northern Europe offing people plots of land in the western territories that were often occupied by Native Americans who had signed treaties with the U.S., and they were also offered jobs in the building of roads, railroads, digging canals,

Following this came the Gold Rush of 1848 in California “gold diggers” moved west across Indian territory and searched for gold on Indian lands along the way. In California alone, according to the article “California’s Little-Known Genocide,” 100,000 American Indians died during the first two years of the Gold Rush, and by 1873, only 30,000 remained.”

Could the clash of civilizations have been avoided?

So again we come to the question of inevitability; “could the clash of civilizations have been avoided?” If we think about President Andrew Jackson’s issuance of “The Indian Removal Act of 1830,” how could it have been otherwise?

The State governments were pleading with the Federal government to remove Native American lands in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Florida, and in many cases, the State militias were wiping out Indian villages, herding men, women, and children into camps to await deportation. The situation in Florida was such that militias from Alabama and Georgia were hunting the Seminoles to capture runaway slaves and acquire land for themselves.

The American government then, to prevent a Civil War, which in fact occurred in 1860, began sending troops into the States to make treaties with the Native Americans, and when these treaties were not honored the Native Americans attacked white settlements, and in return, the U.S. military and the State militias burned villages, slaughtered men, woman, and children, and attempted to capture the warriors who were resisting forced relocation.

In the case of the Seminole Indians in Florida, it is estimated that between 1830 and 1850, 3000 Seminole were killed during the Second Seminole War, and in the continuing “Trail of Tears” march to Oklahoma Territory 4000 Cherokee died, 3,500 Chickasaw, 2500 Choctaw, and 3,500 Creeks who were removed from Alabama.

All of these tribes, with the exception of the Seminole in Florida, were ultimately convinced to leave their ancestral homelands to avoid being wiped out, just as the Calusa were in the Southern tip of Florida in the years after the Spanish departed. As noted on the Seminole Tribe of Florida website, Semtribe.com, the Seminoles in Florida never signed a peace treaty with the American government, and they resisted capture until their number was reduced to around two or three hundred.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is the only Native American tribe that never accepted a peace treaty with the American government, and today membership in the Florida Seminole tribe requires that a person must be “one-quarter Florida Seminole, which means that one of their grandparents must be full-blooded Florida Seminole, and the person must prove direct lineage to a Florida Seminole listed on the 1957 Tribal Roll—records kept when Native Americans were uprooted.”

***